When I lived with my parents in Chennai, I was fascinated by the range and number of wedding invitations they received on a daily basis. I started a small collection of these for fun. This collection later formed the basis of a talk for a St Bride Library conference and a short article for the Ephemerist, Spring 2005. The article titled ‘Matrimonial Times: the design & typography of South Indian wedding invitations’ is republished below.

- – – – –

Most marriages in South India are arranged and while ‘love’ marriages do happen, it is not the encouraged norm. It is an accepted fact for the most part that a boy or girl’s parents will play an important role in the picking of their marriage partner. A marriage in South India is not just the sealing of a bond between two people but a merging of two families. The merger is based on the compatibility of the couple to some extent but important criteria include religion, caste, class, social status and wealth.

Marriage in India is viewed as the culmination of one’s life and great preparations go into making this a grand and memorable social event. It is also a matter of social standing – the grander the wedding, the greater the stature. It is no surprise then that every aspect of an Indian marriage is carefully thought out and planned for months, sometimes years in advance by the families involved. This includes the design of the wedding invitation.

The tradition of wedding invitations

In pre-modern India there was no need for wedding invitations. Marriages often took place within families with cousins marrying each other or within small villages and towns where everyone knew each other. There was no need to inform anyone because everyone already knew of the event. The parents of the bride and groom would simply visit their extended family and friends and family in their homes as a courtesy to tell them the happy news. This served as the invitation.

With economic progress, people began to move away from their ancestral homes into larger cities and things changed. The family unit was no longer contained within the village but was spread out across the country making oral invitations no longer feasible. This coupled with the spread of printing in India in the early 20th century gave rise to these oral announcements being realised in print.

The traditional South Indian wedding invitation is not a card but a printed leaflet that borrows its form from the earlier tradition of oral announcement and from the form of a hand written letter.

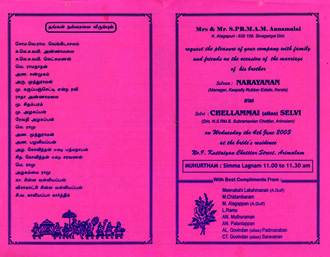

The invitation follows a traditional template and is always enclosed within a large decorative border. It always begins with an incantation to the family’s ancestral god at the top of the invite and is followed by clip art images of five different Hindu gods. The main content of the invitation is worded like a letter and informs the recipient of a marriage between two families.

This is followed by the bride’s and groom’s educational and professional qualifications as well as their family lineage and town. All these details are considered important as it establishes family status and lineage. It also links the past (who the bride and groom are, and where they are from) with the future of the couple. The information about the groom always appears on the left, centred and enclosed within a box while the bride’s details appear similarly in a box on the right. Following this sense of alignment, based on who the invite is from (usually the bride’s or groom’s father), the name of the addressee is placed either to the right or the left.

In general, great prominence is given to the family and often the names of various family members (uncles, aunts, brothers, sisters and cousins) are mentioned beneath the main text as well-wishers of the occasion. While this is portrayed as a visible indication of the family’s support and blessing of the union, it also works like a family tree, outlining lineage for the recipient of the invitation. The details of the actual event such as time, place and date are delegated to the base of the invite and are often in smaller type size. This hierarchy of information is telling because it clearly gives the family prominence over the details of the wedding event.

Traditional invitations are always printed on double-sided glossy art paper, yellow on one side, and pink on the reverse. The main text and images are always printed in dark green and red on the yellow side. Yellow and red in particular are considered to be auspicious colours in the Hindu tradition. Traditionally, the announcements are in the vernacular (in Tamil) and carry very little English text. However, nowadays it is increasingly common practice to have the English version of the invitation printed on the reverse (pink) side of the paper.

Traditionally, these announcements were letter-pressed though they are now also printed by mini-offset or screen-printed. The letterpress process could be partly the reason why the invites often have many different combinations of type. Letterpress jobbing printers very rarely had one complete set of text typefaces, and if they did it was usually Helvetica or Arial. Therefore, to set an invitation with different levels of hierarchy, they often resorted to using display type. A wedding stationery printer in Chennai gave me another reason for this multi-various type palette. Vernacular typefaces, he said (and I paraphrase here) are by the nature of their shape, decorative and script-like. In comparison, Latin typefaces appear ‘austere’ to the Indian eye and therefore require ‘creative mixing’ to match the ornamental feel of vernacular typefaces. Sometimes this creative mixing is done with such enthusiasm that it can involve as many as seven different typefaces in a single invitation.

Contemporary Wedding Invitations

While traditional invitations are still common practice in Tamil Nadu, Hindu families in larger towns and cities go for a more contemporary format. The modern Indian wedding invitation is a riot of colour, typography and image. The invitation, seen as the first intimation of the wedding ceremony carries the responsibility of reflecting the family’s status in society as well as the grandness of the occasion. Invitations (based on the grandness of the wedding and the resources of the bride’s father) take three main forms. The simple card (very rarely used), the folded card (most popular) and ‘the book invitation’. I also looked at envelopes. I was curious to find out a few things.

Which typefaces were most popular?

Did religion made a difference in typographic choice and final form? For example, were the Christians more for scripted faces than the Hindus? Did the Muslims prefer sans serif to serifs? Were the Hindus more ostentatious than the Parsis?

And finally, did the rich have less taste than the poor?

I proceeded to do a little research on this using my collection as a sample.

- – – – –

Which typefaces were most popular?

The typefaces that find most favour for Indian wedding invites are a mixture of serifs, san serifs and script typefaces. They are, in alphabetical order: Amazone, Arial (Regular and Italic), Century School Book, Dauphin, Edwardian Script ITC, Georgia (Regular and Italic), Helvetica (Regular and Italic), Kaufmann, Murray Hill, Nuptial BT, Park Avenue, Poetica Chancery, Pristina, Shelley Allegro, Verdana, Vivaldi, and Zapf Chancery.

Did religion made a difference in typographic choice and final form?

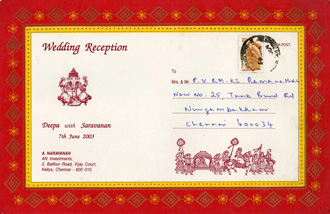

Across all religions and class, envelopes seem to work as brief announcements of the event.

The recipient at single glance is informed of the event (wedding, reception etc.). This is almost usually in Zapf Chancery. They are also informed of who is marrying whom, of the date of the wedding and whom the invitation is from. Hindu cards often carry the address of the invitee as well so the recipient can send a telegram wishing the couple, which is still common practice in many parts of India. In the case of Hindu invitations, the envelope most often carries a clipart image of the Hindu God Ganesha, who is seen to be the remover of all obstacles.

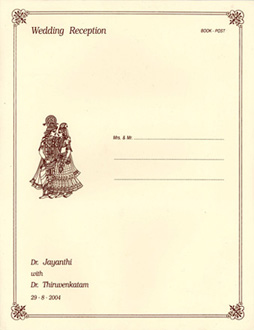

Simple wedding cards

Simple wedding cards were rare to find. In a selection of over 300 samples, there were only four simple card invitations. One was a Christian invite, one a Parsi invite and the other two were Hindu invitations. In general, with both simple and folded cards, Christians and Parsis tend to be more minimalist in their type selection. They rarely go for more than one typeface and the type is almost always in gold on a cream background. If two typefaces are used, one is a script face such as Shelley Allegro. This is used to highlight the names of the parents and the bride and groom. The second typeface is a serif such as Garamond or Georgia for the main body text. There is an European influence evident in these invites.

It is difficult to draw similar parallels with Hindu invites other than the prominence given to the names of the parents and the bride and groom, and the preferred colour for type being red or maroon. This colour preference probably derives from the fact that red or maroon are the colours of the ‘sindhoor’ or the mark that is placed on a bride’s forehead indicating that she is married. Hindu invites also seem to go for serifs or san serifs based on personal preference more than anything else.

The most popular format for Hindu wedding invitations is the folded card. In Chennai, capital city of Tamil Nadu, there are numerous speciality-wedding invitations shops that have pre-designed folded cards for parents to choose from. Only on rare occasions (and with more affluent families) are the invitations custom-made. Numerous samples of invites (with their corresponding envelopes) are pasted within large photo albums and displayed on counters or exhibited individually on the walls. There are helpful assistants to guide parents in their selection. The samples are helpfully categorised by religion: Sikh cards, Muslim cards, Christian cards, Hindu cards, and Interfaith cards.

They are also categorised by levels of grandeur (plain wedding cards, designer wedding cards, scroll invites, and cards with jewels). None of the invitations contain any typography and the first choice of design is based on paper, image and colour. The front of a folded card also never carries any text (though I did find a marvellous exception to the rule).

Grand designs using plenty of gold or silver are usually popular. With Hindu invitations a clipart image of Lord Ganesha is common. Only after the choice of the card is made does type come into the picture and even then it is of secondary importance. Parents are more concerned with the content than the typography and the choice is often one recommended by the salesman behind the counter. With Hindu invitations in South India, three typefaces win hands down – Zapf Chancery and Arial Italic or Helvetica Italic. Zapf Chancery is used for the main body of the invite. Arial Italic or Helvetica Italic is used for more factual information such as lineage, address, profession, educational qualifications. The type again usually appears in maroon or red.

On the insides of the cards, the text is always centred, never in capitals and never in black, which is considered an inauspicious colour; this applies to all cards whether grand or simple, from any religion. As with single card invites, the invitee’s names and the names of the couple as with the single card invites are given most prominence in the card. The main difference between the single card invites and the folded invites is that the folded invites often carry the programme of the wedding on the left side of the card. Keeping in mind that weddings are events which affirm one’s social standing in the community, as many details about the wedding are mentioned even down to the orchestra that has been hired to play at the event.

After the choice of type has being made, the cards then go through a swift proofing session (usually on the very next day) and are screen printed with the approved text. The turnaround time for these invites is usually 48 hours. So if you’re having a shotgun wedding in India, you’d still probably be able to get the invites out in time!

Do the rich have less taste than the poor?

With affluent families, ceremonies for Indian weddings can often stretch over 4-5 days and invitations can often be confused with books as each ceremony demands its own invite.

The invitations are grouped, sized to work as a set and encased in a grand folder. This style of invitation probably provides great relief to parents as all family members can be appeased by the placement of their names on at least one of the many invitation cards. The design and typography of these invitations seems to have no limits as each invite tries to outdo the last.

It is in these custom-made invites that the Indian love of technology comes through. Invites are die-cut, handmade, gold foiled to make them appear as grand as possible.

Sometimes even semi-precious stones and miniature Hindu gods are stuck onto the invites.

The biggest difference between South Indian wedding invitations and Western wedding cards is the focus. While western invites go for the more minimalist, simple and elegant look, Indian invites focus on imbuing the card with the splendour and grandeur of the occasion. We all know what ‘happily ever after’ means in the Western context. But what does ‘happily ever after’ mean in the context of a South Indian arranged marriage? I suspect it is Zapf Chancery in bright, shiny gold!

ephemera,India,typography,-